The In-Between

- Fionn Curran

- Nov 19, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Jan 21

The most meaningful spaces are often the least spoken about – the spaces that are unintentional, inconsequential, afterthoughts. The sliver of space between a barn and a shed, the boundary wall, or the hedge that has been pushed back behind the fencepost. These are in-between spaces, spaces of passage, of transition, of reflection.

Contemporary architecture tends to celebrate the building and the landmark. But if we actually look around us, we see a different sentiment. The beauty and wonder often reside between things. The field may be bound by walls or hedgerows, but it’s the gap where a lamb “snuck” his way out, the gate that creaks in the wind, and the rickety stile with the wonky step that create the wonder and catch the eye. It is not the enclosure that we remember, but the threshold.

A humility lies within these spaces – they are rarely ‘designed’ in the modern sense of the word. Nobody drew a road plan for the bóithrín with grass down the middle. An engineer did not calculate flow rates for the grass ditch. Yet these spaces emerged nonetheless, over generations. They are genuine responses to the terrain, to weather, to the needs of the user and inhabitant. These spaces are where architecture merges with memory, with land, and with life. These spaces are not spaces of architectural assertion, rather ones of accommodation and coincidence.

They are a result of necessity and circumstance, and they do not try to be monumental. Children hide in them, dogs wander through them, elderly neighbours lean over them for a chat.

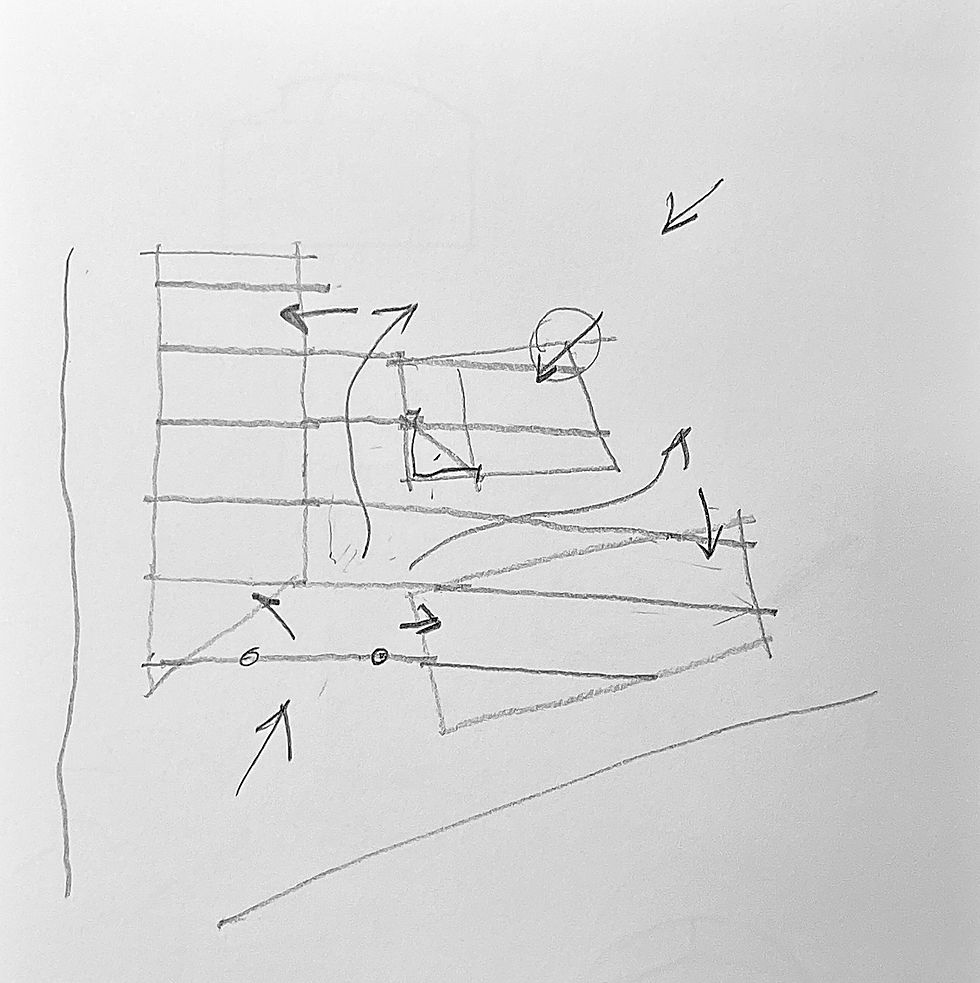

As we often find ourselves working in rural settings, we find ourselves asking the question – how can we design with these intermediate spaces, rather than dismissing them as futile, unconsidered spaces? Can we build upon their past and the intuition in their use? Could we even create new spaces like these with the same patience and care?

In the contemporary world of specification and efficiency, we must resist the urge to over-define. Perhaps a radical architectural ethos is to leave some spaces unresolved. To accept that not every space must have a function, a name, or a square meterage. To accept that sometimes, the space in-between is where life actually happens.

The gap between outbuildings becomes a place to stand in the rain. The hedge not only keeps livestock contained but becomes a habitat for countless families of birds, insects and plants. The dry stone wall becomes a bench, a windbreak, and a home for mice and memories alike.