'As Lived' Drawings

- Fionn Curran

- Nov 19, 2025

- 2 min read

As part of my studies in my fourth year at SAUL, I took part in an elective called ‘Building Land’ – an elective which sought to meticulously and intensely document, draw and represent a partially-disused farmyard and cottage in Co. Kerry. The elective was based on the idea of looking at something slowly, carefully and for a long time, and using this technique to gain understanding of the processes involved in the growth, use, and subsequent disuse of the farmyard and cottage.

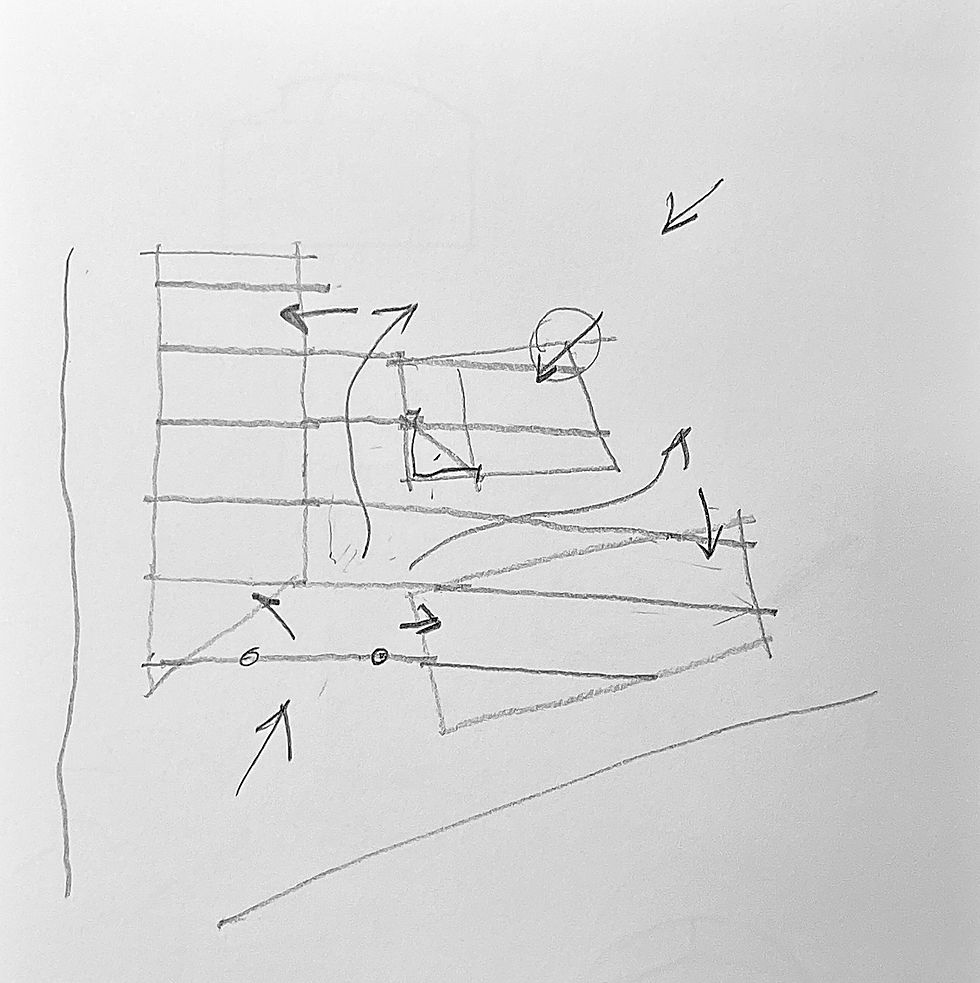

Dr Anna Ryan Moloney MRIAI and Morgan Flynn MRIAI led the elective, and in the end we produced an amazing collection of painstakingly precise drawings of the farmyard, exactly as it stood on the day – warts and all. Every speck of rust, every blade of grass growing through the cracks in the concrete, and every broken slate were photographed, sketched and drawn up. The booklet was filled cover-to-cover with intricately detailed plans, sections and elevations of every building and feature on the site, as well as brief text descriptions of each element. I’ve always thought of the booklet as a series of ‘as lived’ drawings, representing a more realistic snapshot of rural Irish life and its finer details than we are often shown.

What started as an exercise in cataloguing and understanding the slow, progressive, nature of traditional Irish construction, for me became something more. The booklet we produced, while technically rich, is more than just a documentation of the site’s construction. Through the intense study of the site and cottage, the project became a story, a family tree, a biography. The site belongs to Anna’s family, and thus our exercise grew from a simple college project into a deeply personal storytelling across multiple generations.

The partial disuse and disrepair of the site led me to contemplate its future. I fear that if the site is ever sold, or handed down to someone more removed from the past family life on the site, that the importance of the buildings may be lost and the buildings irreparably altered. Often, we as a society are too quick to dismiss things as broken, outdated, in need of replacement by something ‘better’. We must try to part from this notion, as we enter an age of re-use and sustainability across all facets of life.

Working with old buildings on extension or refurbishment projects, we as a practice often find ourselves contemplating the history and heritage attached to these structures. Even if they’re a tumble-down outhouse or a humble byre, these structures have (or had) immense importance to someone at some point in time, and we always strive to honour that and maintain a great sensitivity towards the building’s past.

There is always a temptation to make your work the centre of attention, but we must remember that like the past inhabitants before us, our work will eventually be handed down, and we hope that our work will have the same impact in the future as the rich buildings we work with today.

The elective began as a simple documenting exercise, and ended with the deep contemplation of the nature of heritage, of refurbishment and even the nature of construction itself. Many will be familiar with the concept of ‘as built’ drawings, but this elective introduced me to the power and importance of these ‘as lived’ drawings.